Review Issue 2

Ghostographs:

An Album

Written by Mar (Maria) Romasco Moore

Rose Metal Press, 2018, 88 pp., 978-1941628157

"The stories in Ghostographs are driven by their characters, people like the glowing girl or the man who died from lack of purpose, distinguished by a feeling of memory wrapped in childhood wonder."

A Gallery of Puzzle Pieces

Review by Bryce Delaney Walls

Ghostographs: An Album is a novella-in-flash from author Mar (formerly Maria) Romasco Moore, whose other works include a novel, Some Kind of Animal (Delacorte Press, 2020), a children’s book, Krazyland (Delacorte Press, 2022), and a young adult novel, I Am the Ghost in Your House (Delacorte Press, 2022). Each story in Ghostographs is accompanied by a photograph that inspired the narrative. Moore's intriguing collection presents endless phenomena, inviting you into a strange but welcoming world.

This book is an eerie coming of age story. Ghostographs is filled with snippets of childhood stories that hold surreal heat inside them. Pieces like “The Woman Across the Way” and “My Father” create this hazy veil that is both mysterious and intriguing. They make us stop and consider the strange perceptions we collect as children and how those can be translated into stories about snake-veined women or fathers who fish for ghosts. Meanwhile, there are other pieces like “The Castle” that, although steeped in mystery, don’t expand on our childhood visions. Rather, they expose how places lose their novelty over time.

The accompanied photo and consistent narration immerse us into the world, making each story an unveiling of the peculiar town Moore has built. Every phenomenon is so unique it feels like each page reveals a new piece of the town, with an endless supply of tales left to be discovered. Ghostographs dug up childhood memories I had forgotten. “The Man and The Lamp” reminded me of an abandoned house my cousins and I would pass on our way to school. The house was completely furnished, as though someone were still living inside, but no one had stepped foot in it for years. My cousins and I would try to scare each other by coming up with sinister stories about what secret the house held. Similar to the way Moore constructs Ghostographs’ photo-constructed world, my cousins and I contrived a mythos of stories surrounding this house through the power of our imagination, giving the old home a surreal feeling of nostalgia and curiosity that sticks with me to this day.

Although some stories can trigger these homegrown memories, others dive into darker regions. “The Bridge Over the Abyss” is a piece about depression and the monotonous trap of small-town life. The photo feels ominous, showing an individual standing in front of an old stone bridge. The entire background of the photo is dark; it’s almost impossible to see anything beyond the bridge, a sentiment translated perfectly into the story. The description of how the townspeople worry about this old bridge while simultaneously being proud of an all-encompassing abyss is a fantastic insight into the peculiarity of the town. The speaker details how those who fall off the bridge are only remembered for a short time. Although missed, they become just a part of the mass of souls at the bottom of the abyss. This piece is surreal, scary, hopeless, and beautiful. It’s a story that will make you think about how we mourn and how permanence only exists in memory.

The stories in Ghostographs are driven by their characters, people like the glowing girl or the man who died from lack of purpose, distinguished by a feeling of memory wrapped in childhood wonder. The images themselves are captivating: “Hide and Seek” is paired with an old, yellowed image of two children standing in a field of waist-high weeds. I found myself lost in the image before even getting to the story, wondering where it came from, who these children were, and who thought of taking the picture in the first place. This is where I find the brilliance of Ghostographs: Moore took these photos and asked the same questions, creating a world for us to travel through. The images breathe an old forgotten life into the book, and then the texts display the memories for all to see. We’re enabled by these tales to return to our own ghost stories.

Ghostographs is for people with active imaginations. If you are someone who gets lost in the small details of literature, then each page of this book will be a whole new world to explore. Whether it’s a glowing girl or a dog possessed by a dead husband, a character will catch your interest and draw you onto the edge of reality where Ghostographs exists.

This book will challenge the way you remember childhood, those earliest sensations that are steeped in unknown magic. It will show you how pictures can build a world based on minute details. It will ask you to climb down its dangling chains into its secret-filled town and leave you wondering how to get out again.

I Have the Answer

Written by Kelly Fordon

Wayne State University Press, 2020, 188 pp., 978-0814347522

"I Have the Answer provides a compelling look into Midwestern suburban life from a kaleidoscope of thirteen viewpoints."

What is the Question?

Review by Des Lord

Kelly Fordon’s short story collection I Have the Answer is her second book of fiction and her fourth published work. Fordon has another award-winning short story collection, Garden for the Blind (Wayne State University Press, 2015), and two collections of poetry: The Witness and Goodbye Toothless House (Kattywompus Press, 2016 and 2019). I Have the Answer provides a compelling look into Midwestern suburban life from a kaleidoscope of thirteen viewpoints. Although the stories themselves are not connected and each stands on its own, they connect through the central theme of coping with the roller coaster of ups and downs of everyday life.

Twelve of the stories in I Have the Answer conform to the tenets of realism. One outlier, “The Phantom Arm,” is speculative in nature. In “How It Passed,” the reader follows a group of mothers through sixteen years of their lives, with each year announced in subheadings. Each story takes a unique approach to discussing the diverse nature of life in the Midwest, specifically in Michigan where Fordon is based. The book's title reflects the way in which each story conveys a lesson. The protagonist begins by believing they “have the answer” and ends up learning a different lesson.

An instance of this is in the opening piece, “The Shorebirds and the Shaman.” This story, which sets up the overarching theme, follows Corinne, a recent widow. Her college-age son Scott and a psychologist friend Anne both have observed Corrine’s declining mental health over the past six months. She has rarely left the house since the death of her husband. Under the guise of a girls’ trip, Anne takes Corrine to a retreat where Anne and other psychologists will learn about constellation psychotherapy. Corrine’s reluctance to participate slowly dissolves, and readers get a sense by the end of the story that she is starting to understand her grief, opening the door for her to eventually find the strength to speak to others about it.

“The Devil’s Proof” features a first-person narrator, Marie, who is a fifteen-year-old junior at an all-girls Catholic school in Washington, D.C. One element that sets this story apart is its interest in horror. The narration mentions The Exorcist and behind-the-scenes trivia about it, namely that Marie’s school is near Georgetown, where the film was made. Marie mentions developing a fear of demons after watching the film, which comes into play later in the story with the very real horror of a demon, a college-age boy who does unspeakable things to Marie.

These stories are only two examples of the exemplary work in I Have the Answer. “Jungle Life” and “Where’s the Baby?” focus on narrators with family members who have mental illnesses and features the struggles and self-imposed obligations of being a familial caretaker. Parenthood is a central feature in “How It Passed,” “Afterward,” “Superman at Hogback Ridge,” and “Why Did I Ever Think This Was a Good Idea?” “Tell Them I’m Happy Now” and “In the Doghouse” deal with mental illness in the narrator’s circle of friends. Along with “The Devil’s Proof,” two other stories feature teenage or preteen protagonists, “The Phantom Arm,” where a seventeen-year-old boy wakes up one morning with a third phantom arm that only he can see, and “The Visit: Summer 1976,” where an eleven-year-old girl is forced to help host her same-age cousin over the summer.

This plethora of viewpoints offers many shining gems of insight into the inner lives of characters working through emotional—and, sometimes, physical—trauma. This collection not only covers these topics honestly and simply, but also demonstrates how to skillfully end a story. Fordon’s endings cause the reader to continue thinking about the story and the characters long after the story is done. In each case, Fordon offers an answer to her readers. Although there is no one answer to the difficulties of life, learning from our own experiences as well as others' helps us to discover answers to the questions we should be asking.

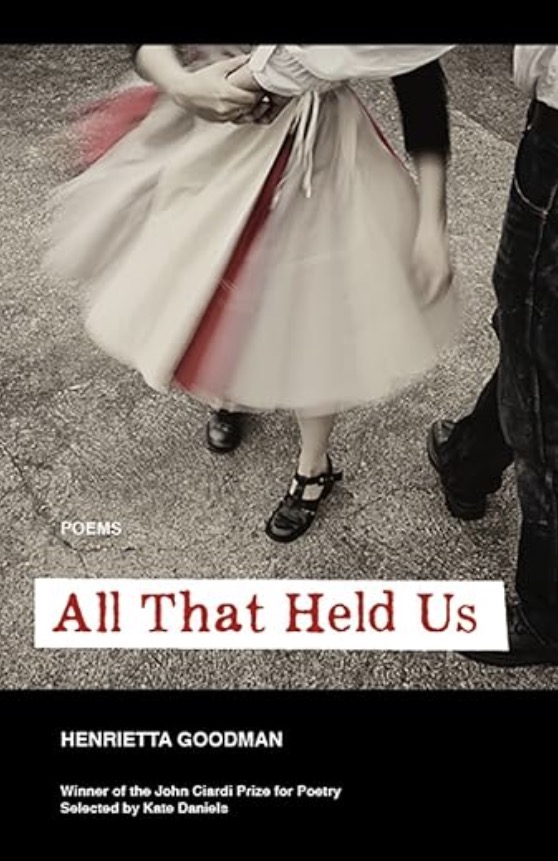

All That Held Us

Written by Henrietta Goodman

BkMk Press, 2018, 66 pp., 987-1943491127

"She provides a reminder that even in the ashes, the remaining embers can light the flames of a bright future."

The Girl in the Mirror

Review by Josie Polizzotto

All That Held Us is Henrietta Goodman’s third book of poetry and winner of the 2018 John Ciardi Award. Her other works include Take What You Want (Alice James Books, 2007), winner of the 2006 Beatrice Hawley Award, and Hungry Moon (University Press of Colorado, 2013). All That Held Us is a reflective collection of Italian sonnets following a tight-knit cast of characters through the exploration of family, womanhood, intimacy, and coming-of-age. Separated into three parts, the sonnets are fresh but remain true to form. Each untitled sonnet exists as one piece of a sonnet cycle, using a meaningful phrase from the previous piece as the first line of the new poem. This deliberate choice allows the story to unfold seamlessly, characters and themes interweaving from one page to the next. I found myself utterly delighted by these poems; the writing is delicate yet raw, recounting the deliberations of a girl navigating newfound senses of love and loss.

The narrator, Mary Anne, explores her youth through the first two parts of the collection by describing her relationship with her mother and “crazy aunt,” as well as her estranged father. Mary Anne’s mother is a woman grappling with her worth and place in the world after the estrangement of her husband. “Mistress / of condescension, she refused to show / me how to want: idealize a man / or love his unfulfilled potential, kiss / the stupid scar that proves him no hero.” Attempting to guide her daughter through the challenges of life, she often projects her own disillusionment of her experiences onto Mary Anne instead. Mary Anne’s father, who has three other children from three separate women, is a Vegas-gambling, Macbeth-loving man with little space in his heart for his family (“…to him gone was the same as dead, / and so he didn’t follow when we went”). Sprinkled throughout are sonnets concerning her aunt, who sprays Lysol when Mary Anne has company over and has a disposition to look down upon her niece as nothing more than “the child.” These inclusions add a fascinating, if not humorous, tone that suggests a God-fearing woman who wears a “shiny treble clef / pinned to her blouse” and has years of memories stock-piled in her room, not barring some moldy bread.

Although anyone will find the beauty in this collection, it is directed toward women of all ages. Teenage girls can relate to Mary Anne’s complicated relationship with her mother, as well as her experience of first love and physical intimacy. Adult women can relish in the reflections on how girlhood and youth impact later life, including the choice to marry and have children. However, there exists something for everyone, whether it be relating to Mary Anne’s distant relationship with her father, odd interactions and dynamics within the family, or the process of gaining wisdom through growth and reflection.

Goodman’s introspection on love and intimacy is remarkably tender and direct. Mary Anne begins by exploring these ideas as a child and challenges her mother’s view on pleasure. “My mother called orgasm a release / of tension—bland and abstract, more like pain / than the second heart, the wild bird I found / in me—fluttering, mysterious pulse.” However, she finds herself married toward the tail-end of the collection, repeating a similar cycle to that of her mother: betrayed, pained, and alone. Mary Anne’s struggle with family and cycles is deeply complex. By forming an identity separate from her mother and attempting to understand her father, she can reflect soundly on her relationships. “I packed some pictures I found in a drawer… / one more / of him with me – a baby whispering / a secret in his ear, my fingers pressed / over his lips. They loved each other once, / and here is proof.” Goodman paints a picture of girlhood and coming-of-age, using deft strokes to create breathing characters and deep contemplation. She provides a reminder that even in the ashes, the remaining embers can light the flames of a bright future.

Carry You

Written by Glori Simmons

Autumn House Press, 2018, 186 pp., 978-1938769290

"Spanning generations, cultures, gender experiences, and even moving backwards and forwards in time, Simmons’ kaleidoscope of perspectives is curiously intimate."

Worlds Collide

Review by MariJean Wegert

In her tender exploration of the inner worlds of four families broken by war, Glori Simmons weaves a tapestry of love and longing. With her gentle narrative style, Simmons focuses on the thought life of the characters revealed in their day-to-day encounters. The complex narrative unfolds through eleven short stories and as many points of view. The story revolves around a single moment: a chance meeting between Clark, an Iraq war veteran returning home to the West Coast with legs full of shrapnel, and Leila, the daughter of an upper-middle class family living in occupied Baghdad who defies the wishes of her traditional family to pursue a romantic relationship with a lower-class man. The moment of their meeting is fraught with the complexity and depth of their secrets, desires, and wounds—and the rippling effect their choices have on one another and the worlds they inhabit.

Leila belongs to the Khalils, an upper-class family entrenched in war-torn Baghdad. Their daily life involves elaborate art events at the museum where Leila’s mother works. In a city wracked by war, the family lives through horrific events while also carrying on with their normal activities: water shortages alongside luxurious romantic affairs and car hijackings while submitting transatlantic college applications. Clark’s family is haunted by their own version of traumatic events after Clark comes home with PTSD. Simmons expects the reader to connect the dots as she patiently reveals the stories of the characters and their connections with one another. Spanning generations, cultures, gender experiences, and even moving backwards and forwards in time, Simmons’ kaleidoscope of perspectives is curiously intimate. She exposes the universal nerves of human longing while attempting to circle closer to the ever-evasive definition of love.

Simmons’ style is gentle, yet her themes of gender expression and culture are persistent. Simmons illuminates the burdens of women who love men who have been discouraged and vilified for masculine self-expression common to the culture. She also explores the deep, quiet wounds of these men for whom masculinity is aligned with violence, leaving them without tools to process their inner worlds. In her second story, “Misunderstandings,” Simmons takes us to Clark’s childhood world. Wishing to avoid the discomfort of sitting by his grandmother on her deathbed and feeling the equally urgent need to use the restroom, he escapes from his mother and wanders the halls of the hospital. In “She’s Your Mother,” Clark comes to realize his mother’s love is not about him. Simmons contrasts Clark’s mother with his girlfriend, Sylvie, who faces more squarely the haunted change in her beloved. Sylvie resolves to honor her own needs instead of shouldering a burden she could not carry. Sylvie approaches the heart of one of the novel’s questions: “She couldn’t figure out what the men in her life wanted from her” (131). This interplay, rooted in cultural expectations, exposes the feminine longing to nurture and protect the combat-weary men who don’t know how to face their own demons, expecting the women in their lives to stand in for their own inner work.

Simmons reveals with generosity, gentleness, and patience the perilous intersection of the emotional and practical worlds of her characters, with many surprising moments coming through the dialogue or thought life of the characters and their relationships with others. One of the difficult insights of the book comes through in the scene after which the collection is named, when Clark’s combat friend says, “What is love anyway but the desire to let someone know you?” (47).

Stiff

Written by Steve Hughes

Wayne State University Press, 2018, 173 pp., 978-0814345887

"Whatever kind of desire he is writing about, Hughes has the incredible gift of putting into words what we’ve all felt but never named."

A Universal Masculinity

Review by Cassandra Felten

Steve Hughes lives in Hamtramck, Michigan, an enclave city in the middle of Detroit. Stiff, an entry in the Made in Michigan Writers Series, is his first collection of short stories. He enjoys a career as a carpenter while editing his Michigan-based zine, Stupor. Hughes’s writing has previously been featured in Fence, Hypertext, and A Detroit Anthology.

Stiff is a group of tightly knit stories connected through their crude, pessimistic, insightful themes focused on sex, desires, primal humanity, masculinity, and unfaithfulness. Every story involves sex, and most involve an affair. The glue holding the whole collection together is this instinctual, primal desire and the understanding of what it does to a man. Will he travel for miles by horseback to get to the woman he fell in love with? Will he order a sex robot to replace his ex-girlfriend? Will his jealousy lead him to fly away in a bird suit? These are all choices the characters in Stiff make, all in the name of simple, universal human desire.

Another piece of the Stiff puzzle holding the stories together is that many of Hughes’s characters are artists. There are musicians, painters, poets, and they all have something else in common besides sexual passion: their desire for their craft is overpowering, as well. While sexual and romantic desire is described as a transcendent experience inhabiting more than one’s body, the artistic pursuit of their craft is an out-of-body, necessary experience involving more than desire. The narrator of “Dexter’s Song” says of playing saxophone with his friend, “Every time we played, I felt my soul rising through my skin and filling the room.” Another example comes from “A Perfect Song,” in which the narrator is a DJ at a bar and dancing to his tunes: “I invert myself, so I am more feeling than I am skin. I forget my body. I become the song. I go inside it and wear it like clothes.” Fellow artists of any kind, whether musical or otherwise, will likely relate to such descriptions.

Hughes writes compelling, sometimes wacky scenes, but the surrounding plot always returns to the main character. Their individuality is accentuated by the choice to put every story in first person; they all feel so real and personal. Another way Hughes makes this feeling of envelopment possible is through the omission of quotation marks when anyone speaks. The choice makes the stories feel less like they are happening in front of the reader and more like memories being played out in the head.

I would classify Hughes as experimental, although easy to read. His surreal style is quite humorous. Some stories feel grounded, like real life, though the events are still always energetically dramatized. In other stories, magically unrealistic events occur. Readers are greeted with the story “Lucky F***ing Day,” which features a man with a pumpkin-head getting scooped out and carved like a Jack-o’-lantern. Toward the end of the book, “Wood for Rhonda” shows us a man with a witch for a wife who, in response to the narrator’s erectile dysfunction, casts a spell on him to turn him into a hard, wood-like man. With or without the fantasy-like additions, the feelings, instincts, and vices of people are exaggerated.

The book is clearly targeted at a male demographic—the back of the book says “masculinity” at the top in red—so male readers might be able to understand and appreciate the subject matter more than women. But I, as a woman, greatly enjoyed imagining I could be like Hughes’s characters; even a female reader doesn’t have to feel left out. Hughes’s descriptions are not solely attributed to the desires of the narrators. They define feelings that everyone, regardless of sex or gender, has felt as human beings. Still, it must be said that this is a collection for adults, based on adult language and explicit sexual content throughout. Lovers of contemporary writing, especially work that playfully engages abstraction, will praise Hughes’s work.

Whatever kind of desire he is writing about, Hughes has the incredible gift of putting into words what we’ve all felt but never named. With the strange twists the stories take as well as beautiful and relatable writing, Stiff is a collection that captures a reader’s imagination. Because many surreal stories take place in a world outside our own, it’s like traveling to a new place each time you pick up the book.

Crude Angel

Written by Suzanne Cleary

BkMk Press, 2018, 88 pp., 978-1943491179

"Whoever yearns for youth or searches for wisdom should read this book."

Nostalgia and Narrative

Review by Robert Simons

In Crude Angel, Suzanne Cleary effectively combines themes of nostalgia, tragedy, desire, and comedy into a collection of poems as stunning as they are comforting. As a seasoned poet and art enthusiast, Cleary is highly skilled at translating memories and objects into narratives and miniature epics. The poems in this collection are linked, not by setting, character, or theme, but by the consistent dreamlike feeling they evoke. The reader is taken places they don’t yet realize they’ve been before. They are dealt emotions they don’t realize they’ve hidden from themselves. Cleary strikes a necessary and artful chord with her audience that is vivid yet intangible, like a visible ghost bringing vital messages from the past.

The poems’ well-chosen titles provide insight into their meaning. Each poem is idiosyncratically distinct. Some poems pay homage to various writers, actors, musicians, and artists, such as Gertrude Stein, Giorgio Morandi, Lawrence Welk, and Morgan Fairchild. In “Poem for Achille Degas,” Cleary portrays Achille Degas in the moment he painstakingly poses as a man fallen off his horse for Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey, a painting by his much more famous brother, Edgar Degas. This poem is not only an example of Cleary’s swift flow of language, moving from stanza to stanza like paintbrush strokes, but it also displays her focus on the modest and seemingly insignificant aspects of life. Through the written word, Cleary immortalizes the humble Achille Degas in a manner far more personal than his own brother had in painting.

This refreshing emphasis on the unostentatious is extended, not just to people, but to things. Whether it be a “mustard-yellow denim jacket” or a “purple cotton dress,” sentiment trumps ornamentality. Cleary affords sentimentality and nostalgia the power to build bridges between seasons of love and life. Such potency is contained within a simple and dated plaster bust of Albert Einstein in the poem, “You Never Know.” It reads, “There is no choice but to stand close / in a crowded junk shop. / My coat sleeve touches Einstein’s hair // and, you never know, I remember / being carried on my father’s shoulders, / remember Karl Walenda on the high-wire // with his daughter on his shoulders. . .” Reminiscence is joined to the present moment, and together they are joined to love. Such is Cleary’s craft.

Some poems are both sides of a coin at the same time, either by balancing satire with emotion, or by compounding memory with future vision. The most fluent of these include, “One-Day University,” “Horse Jacket,” “Perseids Meteor Shower,” “Lassie,” and “My Father’s Feet.” Not a single poem in the collection falls short in the endeavor to enter the reader’s thoughts. Like a “Woodpecker” (“Tree-clung, chisel-billed, wood-boring bombard”), even when they are insistently knocking, they embed a sensation of serenity in the reader’s mind, an experience of “spring’s interior,” and sometimes they provide them with a tear and a laugh along the way. Whoever yearns for youth or searches for wisdom should read this book. Anyone who appreciates eloquence will be more than satisfied with Crude Angel.

Personnel for Issue 2

Editors

Josiah "Jo" Hackett

Josie Polizzotto

Contributing Editor

Cassandra Felten

Advising Editor

Dr. Joseph Chaney

Contributors

Cassandra Felten, A Universal Masculinity

Des Lord, What is the Question?

Josie Polizzotto, The Girl in the Mirror

Robert Simons, Nostalgia and Narrative

Bryce Walls, A Gallery of Puzzle Pieces

MariJean Wegert, Worlds Collide